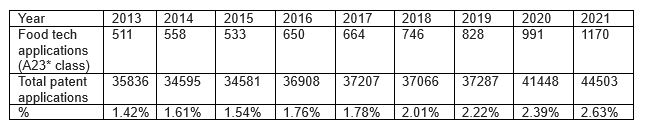

The food manufacturing sector is the largest of Australia’s manufacturing industries, and has experienced significant government investment and growth in recent years[1]. Alongside this, patent filings in the food technology field in Australia have more than doubled in less than ten years, and as of 2021 (the last year for which there is complete patent filing data), 2.63% of all patent filings are in the food technology field[2], up from 1.42% in 2013. The annual figures are shown below:

Not only has there been recent heightened activity in the food technology patent filings, but also opposition filings. In 2023, there were a total of 23 published substantive patent opposition decisions, and of these, five related to food technology – a total of 24% of the decisions. This reflects the high level of monitoring activity undertaken by food technology companies, and the importance of patent filings and opposition activity in supporting innovation and commercialization in the food technology field.

The subject matter of the opposed patent applications also reflects some key trend areas in food technology. Below we review the subject matter and outcome of one food related patent opposition from late 2023. In a future article we will discuss the four other 2023 food technology opposition decisions and reflect on what can be learned from this patent opposition activity in Australia.

In February 2015, one of the Tate & Lyle group of companies based in the USA filed a new provisional patent application directed to a syrup form of allulose. This application formed the basis of an International patent application that became application no. 2016225278 (the “’278 application”) in Australia, which was opposed by Ingredion Incorporated.

To set the scene, allulose is a substitute for sucrose – the most conventional form of “sugar” found in food and beverage products. For decades, researchers and food technologists have worked on a range of strategies to reduce sugar consumption while maintaining sweet taste in manufactured food products. Saccharin was an early sweetening agent that exploded in popularity during sugar shortages in World War I. Other sweeteners in the “high intensity sweetener” class followed, these sweeteners provide a high intensity of sweetness with no calories, allowing for a reduction or elimination of sugar in some food products. Since then, further classes of sugar substitutes and sweetening agents have been introduced – including the functional sweeteners (the most prominent of these being the sugar alcohols – or polyols – such as sorbitol, isomalt and erythritol), and more recently the natural sweeteners, such as stevia. Each class has a range of benefits and detractions – some have the bulk properties similar to sugar, but have a cooling-effect in the mouth or an unpleasant aftertaste. Others have a better taste profile, but without ideal bulk or physical properties.

There is currently increased consumer interest in sweeteners from the “natural sweetener” class. Allulose is one such plant-derived noncaloric sweetener – this class also including stevia, monk fruit and tagatose. Allulose occurs in nature in very small amounts, and has about 70% of the sweetness of sucrose, with only around 5% of the calories, and looks set to become the next “big thing” in sugar replacement.

While the extent of use of allulose prior to the priority date was in dispute, the evidence submitted in the opposition indicated that there had been growing activity in the use of allulose in food and beverage products. Many sugar substitutes are developed in a solid form, to replicate the use of granular sugar used in the home or as a convenient form that is simple to transport. However, Tate & Lyle identified in their patent application that a convenient form of allulose is the allulose syrup form (i.e. a syrup containing allulose dissolved in water). They further noted that a syrup form of allulose is susceptible to degradation over time. The invention claimed by Tate & Lyle in the ‘278 application is an allulose syrup with certain parameters said to provide improved storage stability, those parameters being (i) a dry solids content of from 70% to 80% (a measure of how much allulose is dissolved in the water), (ii) an allulose content of at least 90% by weight (a measure of the purity of the allulose dissolved in the water), and (iii) a pH of from 3.5 to 5.0 (a measure of the acidity of the solution).

The published prior art demonstrated various forms of allulose, and a process for the production of allulose via a liquid syrup containing allulose dissolved in water. However, despite the disclosure of overlapping ranges in the prior art syrup produced in this process, (e.g. the pH of the prior art syrup was said to be in the range of 3.0 to 7.0), the Delegate of the Commissioner found that there was no exact disclosure before the priority date of an allulose syrup with the combination of the required dry solids content, allulose content and pH within the narrower range of 3.5 to 5.0. The Delegate found that the claimed invention was therefore novel and inventive over the prior art.

Ingredion have appealed the opposition to the Federal Court of Australia. The ‘278 patent application of Tate & Lyle was also opposed unsuccessfully by two other parties – Archer Daniels Midland Company and Samyang Corporation. These oppositions remain unpublished for technical reasons concerning confidential information disclosed in the oppositions. However, Court records show that both Archer Daniels Midland Company and Samyang Corporation have also appealed. The appeals are still in progress and we will monitor them with interest.

The ‘278 patent application of Tate & Lyle is one of a number of patent applications filed in Australia over the years that has sought to protect new aspects, uses or presentations of newly emerging sugar substitutes. When a potentially interesting new sweetener is identified, many food companies research aspects of the new sweetener and seek to protect new innovations based on their research. For example, since the 1980’s and up to the present day Wm Wrigley Jr Company (“Wrigley”) filed a series of patent applications relating to chewing gums containing newly developed sweeteners, which have had the potential to block competitor use of those new sweeteners in their own chewing gum products. (See Wm Wrigley Jr Company v Cadbury Schweppes Pty Ltd [2005] FCA 1035 for one example relating to the use of hydrogenated isomaltulose in coated chewing gums.) Coca Cola has also filed numerous patent applications for innovations involving the use of stevia-based sweeteners in food and beverage products (see Spicer Spicer Pty Ltd. v The Coca-Cola Company & PureCircle Sdn Bhd [2021] APO 31 for one example). Such patent filings have multiple advantages – they provide the opportunity to obtain patent protection to keep competitor products at a distance, and they result in prior publication to block competitors from securing patent protection based on later-filed applications covering similar products.

These disputes demonstrate how important it is for food companies to monitor new patent filings to avoid potential infringement risks, and to take action to challenge those patent applications they consider to be directed to non-novel or otherwise obvious applications for newly emerging sweeteners. In light of the upward trend in food technology patent filings, this high level of opposition activity in the field could be expected to continue.

[1] FIAL’s Impact Report March 2024 – https://www.fial.com.au/sharing-knowledge/Final_Impact_Report.pdf

[2] Based on IPC classification in the A23 class, as an indicator of food technology patent subject matter