“My model for business is The Beatles. They were four guys who kept each other’s kind of negative tendencies in check.” Steve Jobs

One of the most enjoyable aspects when crafting an IP strategy is suggesting alternative business models and having clients realise the true potential of their venture.

The choice of a business model is a fundamental decision that affects nearly every aspect of a business, from customer relationships and revenue generation to scalability and risk management. It should be of no surprise that understanding a client’s current or proposed business model is one of the first issues I tackle when interviewing a client for an IP strategy.

My approach is to look at business models to see whether:

- there are impediments in the current business model which could be addressed with IP strategy to enable scalability.

- the current model needs to be adjusted to prevent loss of valuable IP.

- other business models could be developed to secure additional revenue streams through strategic use of IP.

Addressing Impediments

Not having Freedom to Operate (FTO) in a market can be a significant impediment, particularly if it is linked to another’s powerful IP rights. And there are other market barriers to entry such as regulatory issues which need to be considered.

Drilling down into these to determine the size and strength of the impediment (e.g. scope of patent claims), the relevant players (e.g. a regulatory authority) and the “restricted markets” (geographical or subject matter) is the next step.

Then, we can work out whether it is worth tackling the impediments or following the path of least resistance and planning around them.

Practically, a business may not have the resources or inclination to tackle an impediment – such as potential patent infringement. But one tactic is to consider taking on-board a strategic partner that may have the negotiating power or funds to do so.

Impediments can also be internal – such as lack of expertise, money, time and personal bandwidth. Again, drilling down into these can help with internal project management. One example can be timing of the development of an online tool which pre-screens customers enabling internal resources to be freed up.

Making the effort to identify what can restrict scalability and working out how to address that is an important part of an IP strategy.

Adjusting the model

Sometimes an IP strategy reveals that a current business model will not work effectively.

Along with business models, IP strategy needs to be considered in the context of the market as a whole. Therefore, potential loss of IP or lack of control over IP needs to consider the interactions that a business has with other players.

Consider the business model which relies on being first to market and continually innovating to “stay ahead” of competitors. This can work if the business is sufficiently resourced to be market dominant. However, for smaller businesses this is unlikely to be sustainable unless the smaller business puts in barriers to entry (such as IP protection) to deter better resourced competitors which could catch up quickly.

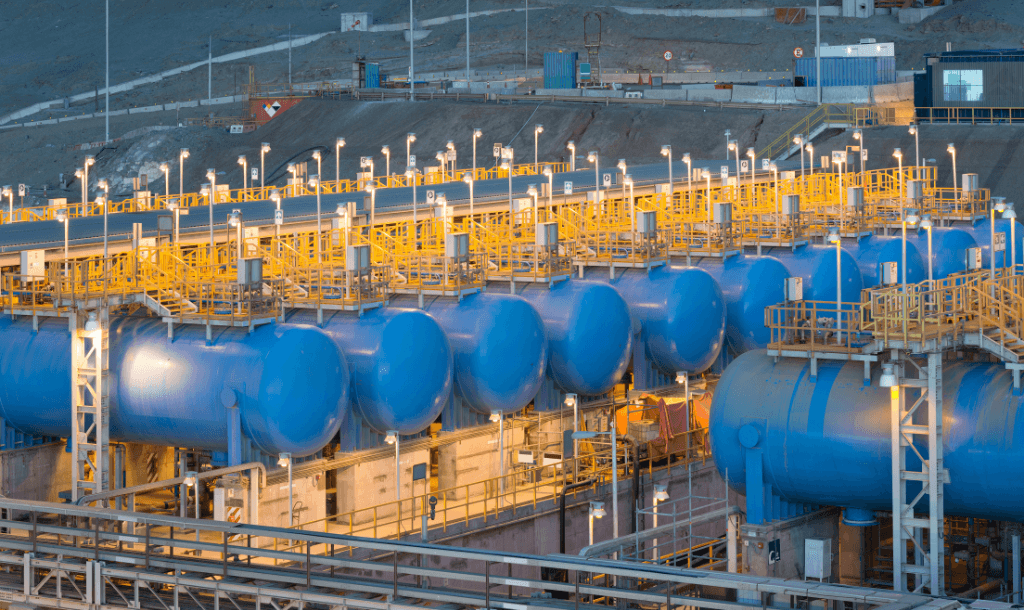

Another business model is vertical integration – namely controlling different stages along the supply chain and bringing production processes in-house. However, if the capital expenditure required for vertical integration is onerous, an alternative model could be to have control over the stages by licensing the IP to external suppliers.

In general, if the model feels “leaky” from an IP sense it needs adjustment to plug those leaks – often by using IP protection as a deterrent or a control mechanism in the market.

Alternative business models

The value of intellectual property can be multiplied or lost – it just depends upon how you treat it.

Alternative business models focus on multiplying the value of intellectual property by exploring different business models and opening up new revenue streams. The start of the process is to understand the core principles of a business, and then see where else they can apply.

For example, a business may have good systems that meet strict regulatory requirements – say in the manufacture of veterinary products. That business could also use or license its intangible assets to enter into other regulated environments (say medical or food).

The business can also recognise that parties in other geographical markets could license their core systems with tweaking for a local regulatory environment – thus scaling up with minimal investment.

Another example is to sell insights from data mining to a wide variety of parties outside of its core business – say advisory bodies.

With reputation being one of the more valuable intangible assets, a business could license its trade marks to other parties with strict quality clauses. In addition to providing additional revenue, this can also build up brand value.

Understanding what the key intangible assets of a business are and then their applicability to other models can open up opportunities that go far beyond those originally envisaged.

Final thoughts

Having a flexible mindset and being able to flip around thinking on business models is invaluable when looking to maximise opportunities. However, this also requires an understanding of IP issues and markets beyond that originally envisaged.