Patent practitioners often grapple with the difficult question of who to name as an inventor in a patent application and, relatedly, what the inventive concept of the application actually is.

According to section 22 of the Patents Act 2013, a patent for an invention can only be granted to a person who is the inventor, derives title from the inventor, or is the personal representative of a deceased person who meets those two requirements.

Since the right to grant extends in all cases from the “inventor”, identifying the person or persons who qualify as an inventor can be crucial to the valid grant of rights. Perhaps unhelpfully, the Act simply defines “inventor” as “the actual deviser of the invention”1 leaving wide open the question of how to determine what qualifies as an “invention” and who qualifies as its inventor.

Matters become more complicated when multiple “inventors” are associated with technology described in the patent. It is common for larger companies and research organisations to employ teams to work collectively on developing new technologies. Project leads can be under internal pressure to identify members as making a significant contribution to the conception and implementation of new concepts, especially in organisations which allocate the proceeds of commercialisation to inventors. External resources may be called upon to contribute in technically difficult and/or highly specialised areas. Yet, determining inventorship in joint collaborations has been described by one court as “one of the muddiest concepts in the muddy metaphysics of the patent law”.2

The right to grant under the Patents Act 2013 derives in all cases from the “inventor”. Getting the inventor wrong could have fatal consequences to a granted patent. In Kennedy v Hazelton [1888] USSC 288; 128 US 667 (1888) it was held (at 672):

Under s.114(1)(b) of the Patents Act 2013, a patent may be revoked if the patentee is not entitled to the patent. Revocation would seem to be the natural consequence of obtaining a granted patent without valid title from the inventor(s). Under s.114(1)(d) of the Patents Act 2014 a patent may be revoked if it was obtained by false suggestion or misrepresentation. That section could be enlivened if a Notice of Entitlement filed under s.73 misrepresents the applicant’s right to grant.

Similar provisions were considered in University of British Columbia v Conor Medsystems, Inc [2006] FCAFC 154 (31 October 2006) with the majority concluding that a patent was invalid if the patentee had not perfected title at the time of grant.

While the Act contains provisions to remedy defects3 (discussed later in this paper) these appear to be contingent on whether, as a matter of law, the patentee was entitled to the patent at the time of grant. A patentee with no valid title under agreement or at common law at the relevant date is likely to be left with no options to perfect title / correct the Register and the patent will be revoked as void.4

In the Full Court in Conor Medsystems, Bennett J dissented and said that the question of entitlement was to be determined at the time of determining invalidity primarily because of the language of the statute (“is entitled” not “was entitled”). The legislative response to the majority’s decision was to add s.22A to the Patents Act 1990.5 It could be said that the addition of s.22A was to confirm that Bennett J was correct as there was no change to s.15. Alternatively, it could be said that the absence of a s.22A equivalent shows that New Zealand law should be the same as pre-raising the bar Australian law. Even if Bennett J were followed in New Zealand, this still leaves lack of entitlement at the time of proceedings and there may be difficulties in perfecting entitlement so late in the day.

So, how do we decide who is an “inventor” and relatedly, what is the “invention”/”inventive concept” they have devised?

Claims based approach rejected

In Yeda Research and Development Company Limited v Rhone-Poulenc Rorer International Holdings Inc and Others [2007] UKHL 43 Lord Hoffman held (at 20):

A claims-based approach to determining inventorship which has found favour in other jurisdictions (notably the US) was rejected by Lord Hoffman because the contribution to a claim may be “non-patentable integers derived from the prior art”. But does this mean that if the contribution of an “inventor” turns out not to be patentable, the efforts expended disqualify them from being named as an inventor? Respectfully, for reasons expanded on below, we think the answer must be no, since the nature of the enquiry should be on the work which is carried out as distinct from the subsequent question of whether the product of the work is, as a matter of law, patentable.

The issue is touched on in an earlier decision of Christopher Floyd QC, sitting as a Deputy Judge in Stanelco Fibre Optics v. Bioprogress (unrep. 1st October [2004] EWHC 2187 Ch) which similarly rejected a claims-based approach to inventorship (at 15):

This statement was specifically endorsed by Lord Justice Jacob delivering the judgement of the UK Court of Appeal in Markem Corporation and Anor v Zipher Ltd [2005] EWCA Civ 267 (22 March 2005) at [103]. Lord Justice Jacob similarly rejected a claims-based approach to inventorship in that case as follows (at [100] and [101]):

From these cases it is clear that the relevant enquiry is “who contributed what” to the inventive concept. But what demarcates an inventive contribution from a non-inventive one in cases more nuanced than Christopher Floyd’s example of merely suggesting you paint something pink?

UWA v Gray: research vs invention

In University of Western Australia v Gray7 the Australian Federal Court was required to determine the ownership of an innovative way of treating cancer using microspheres developed by Dr Gray during the course of his full-time employment by UWA as a Professor of Surgery. Both the Federal Court, and Full Federal Court on appeal8, held that a duty to research did not carry with it a duty to invent and, absent an express provision in the employment agreement which imposed a duty to invent, Dr Gray was under no duty to account to UWA for any inventions, patents, or patent applications.

The decisions draw a distinction between “research” and “invention” on which the lower court said the following:

- Conception is the touchstone of inventorship, the completion of the mental part of inventions.

- Conception is the “formation in the mind of the inventor of a definite and permanent idea of the complete and operative invention as it is hereafter to be applied in practice”. It is complete only when the idea is so clearly defined in the inventor’s mind that only ordinary skill would be necessary to reduce the invention to practice without extensive research or experimentation.

- An inventor need not know that the invention will work for conception to be complete. The inventor need only show that he or she had the idea. The discovery that an invention actually works is part of its reduction to practice.

- It is not the law that the inventor’s definite and permanent idea must include a reasonable expectation that the invention will work for its intended purpose even when it deals with uncertain or experimental disciplines where the inventor cannot reasonably believe that an idea will be operable until some result supports that conclusion.

The propositions set out in Burroughs Wellcome (1994) 40 F 3 1223 define “invention” by reference to completion in concept which distinguishes the invention from its verification and reduction to practice.”

So from these passages of University of Western Australia v Gray we understand that:

- Conception is the touchstone of inventorship.

- There is a difference between conceiving (inventing) and verifying (reducing to practice).

- An inventor need not know an invention will work for conception to have been completed, but

- Conception will be complete only when the idea is so clearly defined in the inventor’s mind that only ordinary skill would be necessary to reduce the invention to practice without extensive research or experimentation.

“Ordinary skill” Brightline test proposed

The contention that someone who merely reduces to practice using ordinary skill an invention conceived by another finds support in a number of other cases. It is submitted that these cases also establish that the reverse is likely to be true – a member of a team who contributes more than ordinary skill to the task of reducing to practice an invention conceived by another will be an “inventor” for the purposes of patent protection – and this will remain the case even if their contribution is subsequently deemed to be unpatentable through lack of inventive step.

If correct this makes the enquiry into the nature of work conducted (ordinary skill or something more?) a useful Brightline for establishing inventorship. That test would involve two simple enquiries:

- Did a team member contribute to the inventive concept?

- If yes, is what they contributed to the inventive concept the product of more than ordinary skill?

Importantly, if extensive and/or prolonged research or experimentation are required to reduce the invention to practice, the enquiry into “inventorship” needs to be ongoing until the inventive concept is fully reduced to practice.

The veracity and application of the test can be Illustrated with reference to two case studies.

Case Study #1: Henry Brothers

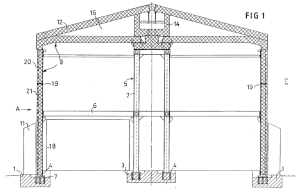

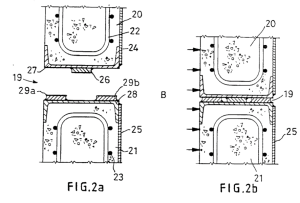

Henry Brothers concerned a complicated claim and counter-claim for compensation for crown use of an invention relating to pre-fabricated blast-resistant buildings in Northern Ireland at a time when there was considerable unrest there. The names of witnesses were even anonymised for security reasons.

The Crown used an experienced civil engineer, Mr Z, to use the invention in the construction of a police station. Henry Brothers, which owned the patent, conceded that Mr Z was a joint inventor, and that the Crown was a co-owner of the patent, but sought compensation for the Crown’s use on the basis that the Crown’s rights as co-owner did not include engaging an independent contractor without its consent to grant the requisite license to exercise the patent rights. The Crown’s response was to apply for revocation on that basis that Mr Z was the sole inventor of the invention.

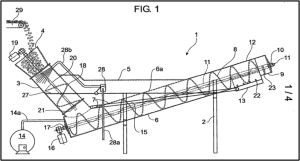

The invention is explained in the following extracts from the granted patent GB 2277334 B ‘Prefabricated blast resistant building structures’:

“This invention relates to prefabricated blast resistant building structures, and in particular prefabricated structures having at least two storeys.

Conventional building structures having two or more floors can suffer substantial blast damage even when subjected to bomb blast of low intensity. The floors of a conventional building structure …can withstand large loads in the downward vertical direction but are unable to resist sideways forces particularly those arising from bomb blast or mortar attacks.

It is the aim of the present invention to provide a prefabricated blast resistant building structure, especially one having two or more storeys, which limits relative movement between different parts of the structure by spreading the load exerted by the blast pressure over a greater part of the structure.

According to the present invention, there is provided a prefabricated blast resistant building structure, the structure comprising exterior walls constructed from a plurality of preformed panels, a roof, and an internal frame structure for supporting the roof and exterior walls, wherein key-joint means is provided at the boundary of at least some of the pre-formed panels of the exterior walls, which key-joint means is configured for limiting relative displacement between adjacent pre-formed panels in a direction perpendicular to the major plane of the panels thereby transferring shear forces from one panel to another to spread blast pressure over the structure in the event of a bomb blast.

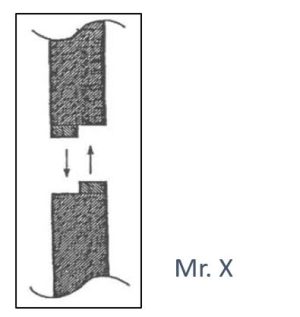

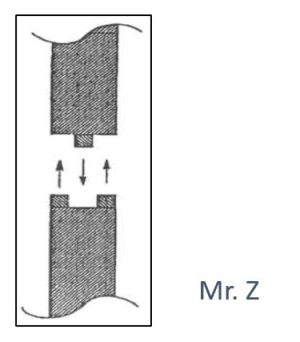

Justice Jacob had found at first instance in the Patents County Court9 that the “key joint means” was central to the inventive concept of the patent at issue. On the facts, Mr. X, for Henry Brothers, had designed a two-plate shear joint.

Following tests conducted, and meetings attended, by Mr. X and Mr. Z in February and March 1993, Mr. Z developed a three-plate key joint.

Lord Justice Jacob concluded that Mr Z, was the sole inventor (at 706):

Henry Brothers appealed. On appeal it did not challenge Jacob J’s finding of primary facts, but challenged the legal conclusion which he drew from them. It submitted the court should identify the “inventive concept” of the claims, and on that approach Mr. X was seen to have contributed the whole of the inventive idea, except that his joint was not a key joint.

The Court of Appeal did not accept that argument, holding (at 448-449):

“I agree that it is necessary for the court to identify the inventive concept, but I think that Mr Purvis’s formulation of his argument exposed its weakness. The exception to which he had to add – that Mr X’s joint was not a key-joint – goes to the heart of the inventive concept (so far as there was an inventive concept at all, and not just a fairly routine application of engineering skill)…

I cannot entirely agree with the judge’s approach in the passage of his judgment (at 706) which I have already set out. I am not inclined to think that the invention was “a combination” of elements. Mr Z saw Mr X’s drawing (at a meeting at which Mr X was not present) and replaced one type of joint (intended to produce a labyrinthine effect) with another type (a key-joint intended to produce distribution of blast pressure, including rebound pressure). Mr X’s drawing of the joint was not so much useless as directed to a different objective. Nevertheless, I feel no doubt that the judge was correct in his conclusion.”

What is interesting in this passage is the parenthesised disclaimer: “so far as there was an inventive concept at all, and not just a fairly routine application of engineering skill”. It supports the proposition that inventorship turns on the nature of the task being performed by the alleged inventor with respect to what has been identified as the “inventive concept” of the specification: and that these assessments (of firstly, work in relation to the inventive concept and, secondly, the nature of that work) might be given equal weighting so that neither:

- A routine application of engineering skill in relation to the inventive concept; nor

- A non-routine application of engineering skill on something other than the inventive concept; will qualify someone as an inventor / joint inventor.

Implicit in the finding of both Jacob J (and the UK Court of Appeal) that Mr Z was the inventor of the key joint, was the factual conclusion that not only did Mr Z work exclusively on the key joint but that Mr Z arrived at the key joint through the application of more than ordinary skill (or, in the words of the Court of Appeal, “a fairly routine application of engineering skill”). It is this effort which demarcates the act of invention from other non-relevant activities relating to the key joint. Likewise, Mr X was not an inventor because, although his efforts to develop the two-plate shear joint may have involved the exercise of more than ordinary skill, those efforts were directed to something both courts found was not the inventive concept of the patent.

Case Study #2: Polwood v Foxworth

The distinction between “invention” and the exercise or ordinary skill is more explicitly addressed in Polwood v Foxworth11. The case involved a dispute between two companies as to the entitlement to the grant of a patent12 which claimed:

“…a method for production of organic plant growth media from sawmill waste, said process comprising the steps of:-

introducing … sawmill waste into an inlet of a conveyor mechanism containing a body of heated water;

submerging said sawmill waste in said body of heated water for a predetermined period of time to kill microorganisms, … whilst transporting said treated sawmill waste towards an outlet of said conveyor mechanism;

and at least partially dewatering said treated sawmill waste to a predetermined moisture content.”

The patent was also directed to an apparatus for implementing the method of the invention. On the facts, a Mr. Rampton discussed with his neighbour, Mr. Connick, the idea of transporting material (bark) through processing equipment (two augers) which causes the plant material to be submerged in treated water. The resultant plant growth medium was then to be dewatered to reduce its moisture content. They formed Polwood and communicated the concept to Mr Power and Mr Kemp of Foxworth under a license. Using the information communicated Foxworth developed the concept by building prototypes and ultimately an apparatus to implement the concept.

At first instance13 the trial judge concluded that Polwood and Foxworth were joint inventors: Polwood of the method and Foxworth of the apparatus. Polwood appealed, contending that there was a single invention the subject of the patent and that is the concept, which it said encompassed both the method, apparatus, and product claims. Polwood recognised that Foxworth first made the apparatus but contended that this was no more than implementing the completed and final Polwood concept. Although not phrased as such this is essentially a submission that Foxworth’s contribution was limited to reduction to practice without extensive experimentation or research per UWA v Gray. The Full Federal Court disagreed:

The Full Court continued:

The Full Court went on to adopt with approval a number of propositions drawn from UK and US jurisprudence. In each of these there is a reference to the nature of the contribution requiring more than simply the exercise of ordinary skill (our emphasis):

In the context of entitlement to a patent a mere, non-enabling idea, is probably not enough to give the patent for it to solely the devisor. Those who contribute enough information by way of necessary enablement to make the idea patentable would count as “actual devisors”, having turned what was “airy-fairy” into that which is practical…On the other hand those who contribute no more than essentially unnecessary detail cannot on any view count “s “actual devisors”.

This analysis complete, the Full Court then considered Australian jurisprudence on joint inventorship14 before summarising the enquiry on appeal (and explicitly adopting the proposition advanced above) as follows:

Difficulties noted, the Full Court was satisfied that Foxworth’s contribution was more than the application of common general knowledge to Polworth’s concept:

These findings confirm the ordinary skill Brightline test as both applicable and correct. Under that test Foxworth was an inventor because its contribution:

Other cases

In its analysis of Australian jurisprudence the Full Court in Polwood v Foxworth adopted15 from JMVB Enterprises Pty Ltd v Camoflag Pty Ltd Ltd [2005] FCA 1474; (2005) 67 IPR 68 a statement from Crennan J at [132] that rights in an invention are determined by objectively assessing contributions to the invention rather than assessing the inventiveness of respective contributions. As advanced above, this is entirely consistent with the statement in Stanelco that “the purveyor of a non-inventive contribution to a working combination may be a co-inventor and that the quality of the contribution and the impact on the result depends on the facts in each case. It is not necessarily the inventiveness of the contribution that is the determining factor.”

The Full Court also cited with approval (at [46]) Yeda Research and Development Co Ltd v Rhone-Poulenc Rorer International Holdings (2008) I All ER 425 in the context of a discussion about whether a claims-based approach to inventorship is appropriate. In Yeda Lord Hoffman also applied the distinction between “invention” and the mere exercise of common general knowledge as follows (at [60])

The statement of the Full Court in Polwood v Foxworth in paragraph 40 (set out above), and the cases relied upon by the Full Court to reach the view that Foxworth was an inventor, in our view support the proposition that the focus of the enquiry as to whether a contribution is “inventive” turns on the nature of the task conducted and not the legal result (ie conferring an inventive step from a patentability perspective) and is a two stage enquiry looking at:

If correct, it means that a non-inventive contribution to the “inventive concept” produced by the exercise of something other than common general knowledge / ordinary skill should give rise to a claim to joint inventorship.

Think about that: if correct it means that inventors don’t need to be inventive from a patentability perspective. This is a proposition which many IP professionals may find difficult to reconcile but the following scenario illustrates how that can occur:

It will be observed that there is no finding in this scenario that D conferred an inventive step in this case because it was already known from the prior art. However, since it wasn’t common general knowledge to add feature D, the second person was properly named as an inventor.

The ordinary skill Brightline remains consistent with, but preferable to, the conclusion in UWA v Gray that:

• inventors are those who conceived the invention, and

• conception is complete only where extensive research or experimentation are not required to reduce it to practice,

because, as noted above, for some inventions it may not be possible to determine if extensive research or experimentation are required until after the reduction to practice has been performed. This means that the enquiry into “inventorship” according to UWA v Gray is in many cases going to be a hindsight enquiry possible only after the invention has been commercialised. Focussing on contributions minimises that difficulty.

Remedies and advice

A patentee with valid title by way of agreement or operation of law at grant has various means to correct the Register to add or remove inventors so that the Register accurately reflects the actual devisors of the invention. Patent specifications can be amended by the Commissioner or the Court under ss.83 and 89 of the Act. However, since the forms on which inventors are named do not form part of the specification, the more relevant provisions are ss.202 and 203 of the Act which provide:

202 Commissioner may correct other persons’ mistakes in patents register, etc

(1) The Commissioner may (on application by any person or on the Commissioner’s own initiative) correct an error or omission that the Commissioner is satisfied has been made by any person in—

(b) any patent; or

(c) any patent application; or

(d) any documents filed in connection with a patent application or filed in proceedings before the Commissioner in connection with a patent or patent application.

(2) Any person (whether or not that person made the error or omission) may apply for a correction under this section in the prescribed manner.

203 Court may rectify patents register

(1) The court may, on application of any person aggrieved, order the patents register to be rectified by making an entry, or varying or deleting an entry, in it.

However, a patentee with no valid title under an agreement or at common law at grant is likely to be left with no options to perfect title / correct the Register and the patent will be revoked as void. Those involved with securing patent rights should therefore take steps as early as possible to:

• Identify the full team associated with conceiving and developing that inventive concept

• Identify the nature of contribution of those team members, and

• Obtain assignments from those team members who exercised more than ordinary skill with respect to the inventive concept identified

Critically the terms of reference of this enquiry should focus on the nature of the work. IP professionals will need to set aside any prejudices they may bring to the task as to the “value” of a team member’s contribution.

In New Zealand it would also be prudent to err on the side of treating team members as “inventors” for assignment and identification purposes. In a section dealing with requests for parties to be entered on the patent Register as an inventor, the British Manual of Office Practice (Patents) specifically confirms that mere mention does not equate to a legal conclusion as to its correctness:

16,3 Such mention is for information only, and has no effect on the rights of any person under the patent, nor is it incompatible with some other person being treated as the true and first inventor for any other purpose under the Act”.

This suggests that there will be no adverse consequence to naming someone as an inventor incorrectly in New Zealand. The reverse may not be true.

[1] Section 5 Patents Act 2013

[2] Mueller Brass Co v Reading Industries Inc 352 F Supp 1357 (ED Pa 1972) at 1372.

[3] Including, potentially, application to the Commissioner under s.83 to amend the specification after acceptance, application to the Court under s.89 to amend the specification after acceptance, application under s.129 for substitution of applicants (which must occur before grant), and application to the Commissioner (under s.202) or Court (under s.203) to correct a mistake in the patent register.

[4] Although outside the scope of this paper, the passage from Kennedy v Hazelton would appear to be particularly apposite for applications made under the Patents Act 1953 for which applicants need to establish a right to apply not a right to grant.

[5] Which reads “22A Validity not affected by who patent is granted to

A patent is not invalid merely because:

(a) the patent, or a share in the patent, was granted to a person who was not entitled to it; or

(b) the patent, or a share in the patent, was not granted to a person who was entitled to it.

[6] As an aside, the reference here to “natural person” would seem to exclude AI from the category of people who can qualify as “inventors”, suggesting that the offices on both sides of the Tasman got it right when rejecting a patent application naming AI as an inventor in recent cases: see Stephen L. Thaler [2022] NZIPOPAT 2 and Commissioner of Patents v Thaler [2022] FCAFC 62

[7] University of Western Australia v Gray [2008] FCA 498

[8] University of Western Australia v Gray [2009] FCAFC 116, (2009) 179 FCR 346.

[9] [1997] RPC 693 (Jacob J.)

[10] Henry Brothers (Magherafelt) Ltd v Ministry of Defence and Norther Ireland Office [1999] RPC 442

[11] Polwood Pty Ltd v Foxworth Pty Ltd (includes corrigendum dated 5 March 2008) [2008] FCAFC 9 (18 February 2008)

[12] AU 2010227018

[13] Foxworth Pty Ltd v Polwood Pty Ltd [2006] QSC 185

[14] Discussed briefly below.

[15] At [54]